Diseases of the Kidneys

Kidney diseases encompass a wide spectrum of conditions that impair renal structure or function. Because the kidneys play critical roles in filtering waste, balancing electrolytes and fluids, and regulating blood pressure, damage to these organs can have systemic consequences. This article provides a patient‑friendly yet clinically accurate overview of kidney diseases, then focuses on how Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is applied in diagnosis and monitoring.

General Overview of Diseases of the Kidneys

The kidneys are two bean‑shaped organs located in the retroperitoneum on either side of the spine. Each kidney contains approximately one million nephrons—microscopic filtering units that remove waste products and excess fluid from the bloodstream. Blood enters the nephron’s glomerulus, where filtration occurs; the filtrate then passes through tubules that reabsorb needed substances and excrete the remainder as urine.

When kidney structure or function is compromised—whether by infection, inflammation, obstruction, tumors, or inherited disorders—waste products and fluids can accumulate in the body. Chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) below 60 mL/min/1.73 m² for three months or more, affects an estimated 37 million U.S. adults (approximately 15% of the population) and often progresses silently until advanced stages (NKF). Acute kidney injury (AKI), in contrast, develops over hours to days, often in response to severe illness, dehydration, or medication toxicity.

Left untreated, significant kidney impairment may lead to fluid overload, electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hyperkalemia), uremia (buildup of toxins), and ultimately end‑stage renal disease requiring dialysis or transplantation. Early detection, accurate characterization, and ongoing monitoring are therefore essential to preserve kidney function and guide therapy.

General Description of Kidney Diseases

Below is a summary of the most common and clinically important kidney conditions:

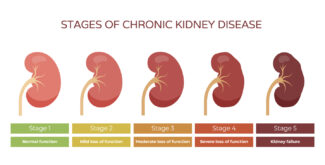

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

CKD is most frequently caused by diabetes mellitus and hypertension. It progresses through five stages, from mild (Stage 1, normal GFR with kidney damage) to end‑stage renal disease (Stage 5, GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m²)( NIH). Early CKD often produces no symptoms; as it advances, patients may experience fatigue, anorexia, nausea, swelling in legs or around the eyes, and changes in urine output.

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

A hereditary disorder characterized by progressive development of innumerable fluid‑filled cysts in both kidneys. ADPKD leads to organ enlargement, hypertension, recurrent infections, and eventual loss of renal function. It is one of the most common genetic kidney diseases, affecting approximately 1 in 500 to 1,000 people (Medscape).

Simple and Complex Kidney Cysts

Simple cysts are common, benign, and asymptomatic—especially in older adults. Complex cysts have internal septations or solid components, which may raise concern for malignancy or risk of hemorrhage and infection (Cleveland Clinic). Distinguishing benign cysts from cystic tumors is crucial for management.

Renal Tumors

Tumors of the kidney can be benign (e.g., angiomyolipoma) or malignant (e.g., renal cell carcinoma, oncocytoma). Renal cell carcinoma is the most prevalent kidney cancer, often detected incidentally on imaging. Symptoms—when present—include hematuria, flank pain, and a palpable mass. Accurate lesion characterization by imaging frequently obviates the need for immediate biopsy (American Cancer Society).

Infections and Inflammation

- Pyelonephritis is an acute bacterial infection of the renal parenchyma and pelvis, presenting with fever, flank pain, and urinary symptoms.

- Interstitial nephritis involves inflammation of the renal interstitium, often triggered by medications or autoimmune processes.

Vascular Disorders

- Renal artery stenosis (narrowing of the renal arteries), most commonly due to atherosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia, can cause refractory hypertension and ischemic nephropathy.

- Renal vein thrombosis impairs venous outflow, leading to edema and impaired filtration.

How MRI Is Used to Diagnose and Monitor Kidney Diseases

MRI offers exceptional soft‑tissue contrast without ionizing radiation, making it an invaluable tool in renal imaging. Its applications span lesion characterization, functional assessment, vascular evaluation, and longitudinal monitoring.

Lesion Characterization

- Cyst vs. Solid Mass: MRI differentiates simple cysts (fluid-filled, nonenhancing) from solid tumors by evaluating signal intensity on T1‑ and T2‑weighted sequences, and enhancement patterns after gadolinium contrast. Complex cysts—those with septations, mural nodules, or debris—require MRI to assess Bosniak classification and malignancy risk (RadiologyInfo.org).

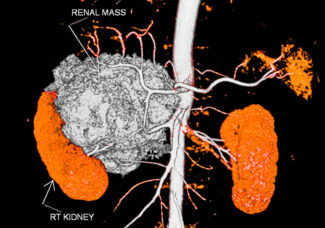

- Tumor Staging and Vascular Invasion: In suspected renal cell carcinoma, MRI can precisely delineate tumor extent, involvement of the renal vein or inferior vena cava, and perinephric fat invasion. This staging information is critical for surgical planning and prognosis (American Cancer Society).

Imaging in Polycystic Kidney Disease

- Total Kidney Volume (TKV): MRI is the gold standard for measuring TKV and cyst burden in ADPKD. Serial MRI measurements correlate with disease progression and help evaluate response to therapies such as vasopressin‑receptor antagonists (e.g., tolvaptan) in clinical trials (NIH).

- Early Detection of Microcysts: MRI’s high sensitivity reveals small cysts undetectable by ultrasound, facilitating earlier diagnosis in at‑risk family members.

Functional and Fibrosis Assessment

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI): DWI measures water molecule movement within tissues. Restricted diffusion may indicate fibrosis or acute injury, offering a noninvasive biomarker of kidney health (NIH).

- Blood Oxygen Level–Dependent (BOLD) MRI: BOLD sequences assess renal oxygenation by detecting deoxyhemoglobin levels; reduced oxygenation suggests ischemic injury or hypoperfusion in CKD.

Vascular Imaging with MRA

- Renal Artery Stenosis: Contrast‑enhanced MR Angiography (MRA) visualizes the renal arteries and can identify stenosis without nephrotoxic iodinated contrast, making it preferable in patients with impaired renal function (JVS).

- Venous Thrombosis and Anomalies: MRA also depicts venous structures, detecting thrombosis in the renal vein and characterizing vascular malformations.

MR Urography

- MR Urography (MRU) produces detailed images of the urinary tract—kidneys, ureters, and bladder—using heavily T2‑weighted sequences or contrast‑enhanced techniques. It evaluates causes of hematuria, obstructive uropathy (e.g., stones, strictures), and urothelial tumors (https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/urography).

Monitoring Treatment and Disease Progression

- Active Surveillance of Small Tumors: For incidentally detected small renal masses (< 4 cm) under active surveillance, periodic MRI (typically every 6–12 months) assesses tumor growth rate and informs decisions regarding intervention versus continued observation (American Cancer Society).

- Post‑Therapy Follow‑Up: After surgery, ablation, or systemic therapy for renal cancer, MRI detects residual or recurrent disease and evaluates treatment response without radiation exposure.

- Tracking Chronic Disease: In CKD or ADPKD, serial MRI exams gauge changes in renal volume, cyst burden, perfusion, and fibrosis, guiding adjustments in medical management and lifestyle interventions.

Greater Waterbury Imaging Center, GWIC, offers comprehensive MR imaging services, including MRI for patients with claustrophobia. Located on the Waterbury Hospital campus with convenient gated parking, we provide fast access to care and accurate imaging results. Contact us for all your MR imaging needs, including MRI for kidney disease diagnosis and monitoring.